24 May 2019

The Building

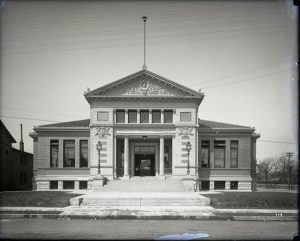

From the collection of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County

From the late-1800s, the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County (PLCH) was beginning to search for solutions to their over-crowded building, downtown. This led them to seek funds from Andrew Carnegie’s foundation. They didn’t get a new main library building, as they wished, but their inquiry led to the building of Cincinnati’s first six Carnegie branches, among which the Walnut Hills branch was the very first built, the largest, and the most funded.

Andrew Carnegie had begun funding libraries and other public institutions in 1881. An immigrant from Scotland, he dropped out of school at the age of twelve to work a series of factory jobs. One of these jobs gained him regular access to the owner’s personal library. Carnegie took advantage of this opportunity to teach himself through these borrowed books and eventually build his own place in the steel industry. These experiences led him to publish his gospel of wealth in The North American Review, in 1889, where he stated that, “a man who dies rich dies disgraced.” In 1901, he retired and sold his business. By the end of his life, he’d given away 80% of his accumulated wealth of $353 million.

From the collection of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County

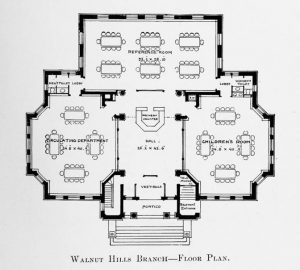

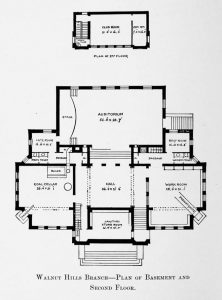

The designs and placements of the Cincinnati Branch libraries were based on Carnegie Foundation stipulations created by Foundation trustee, James Bertram. Communities who requested funds had to furnish proof of need, a suitable site, and local assurance of 10% of building funds to be set aside for annual maintenance. Libraries should be easily accessed by the community, beautifully constructed, and beautifully situated. They were to be viewed as cultural centers, not only housing books, but also providing community programming. Bertram published six different floor plans in a 1904 pamphlet, “Notes on Library Buildings”, stipulating separate reading rooms, a children’s room, a central librarian’s desk for better oversight, an auditorium, and community meeting rooms.

Funding was based on a $2.00/person funding formula according to the latest census. Most grants ranged between $10,000 and $20,000. Funds were issued by the Foundation in three installments: at groundbreaking, completion of the foundation, and completion of the building. Public Library board trustee, James Albert Green, visiting Carnegie in New York in 1901, told the steel magnate, “how lovely were our hilltops and how Walnut Hills had grown out of all bounds since we had cable cars” after Carnegie inquired about the suburbs he had once visited. The board received $180,000 from Carnegie to build their first six branches.

From the collection of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County

The Walnut Hills branch was planned as the most prominent because of the size and importance of the neighborhood, already identified as Cincinnati’s second Downtown. It was built at a cost of $46,150.30 on the southwest corner of Kemper Lane and Locust St. (now Wm. Howard Taft Rd.), a plot acquired from Maria Longworth Storer (Rookwood Pottery founder). Architectural firm McLaughlin and Gilmore won the bid, and French architect Louis Belmont designed the building. Built in the French Renaissance style, using deep red brick, limestone, and a red tile roof, the interior was paneled with birch-stained mahogany. The two columns on either side of the front entrance were imported from Munich. (These and many other original features remain part of the building, today.)

From the collection of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County

The basement housed a 140-seat auditorium and a green room. The third floor contained a second meeting room. The main floor situated the librarian’s desk at the center, with a reference room and a children’s room on either side, separated by glass dividers for easy oversight. Men’s and women’s bathrooms (now offices and a break room) were also built off the main room.

A couple of interesting comments belie differing attitudes among leaders involved in the project at the time based on their views of workers and organized labor. In the 1905 PLCH Annual Report, the board president reported that an iron workers strike “caused an annoying and tedious delay.” When the branch opened, Saturday April 7, 1906, Cincinnati mayor James Dempsey, a Labor Party member, failed to acknowledge Carnegie in his remarks because he had “no deep admiration for a man who has made his millions out of the sweat and blood of the toiling classes, but who attempts to atone for the oppression by giving away buildings, and thus advertising himself as a philanthropist.”

Early Patrons

The Walnut Hills Branch’s 10,495 volumes (including 2500 for children and 400 reference works) were not placed on the shelves until Monday, April 9, two days after its grand opening. Children were invited to a separate opening, Saturday April 14, that included stories from a Miss Pearl Carpenter, while a Miss Julie Worthington spoke about Yosemite Valley, showing stereo-opticon views. These women were presumably librarians, whether for the branch or downtown.

From the collection of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County

Children were the largest initial group of users of the branch (very much as they are, today). Branch Library Department director, Mirpah C. Blair reported, “After the first night it was found necessary to keep the doors of the Children’s Room open until half past nine when the remainder of the Library closed. Even then the other rooms were filled with them. In a short time, however, their curiosity abated and they were satisfied to stay in their own room. The interest of the adults was not so great at the beginning, but it is gratifying to note that it has been steadily increasing until the June report shows an adult circulation nine hundred larger than the juvenile.”

Cincinnati’s branch libraries were built in an era when libraries were changing their attitudes about who should use a library, and how. Many libraries had recently become public institutions, rather than private clubs. In Cincinnati’s Main Library, much of its physical structure required it to operate on an old model that obliged patrons to request a particular book for which a page would be sent to retrieve it. The Walnut Hills Branch library reflected a new attitude of allowing patrons to browse among the stacks, themselves, to leaf through the books where — according to the head librarian in 1905 — “they may acquire, more or less, the library habit, — the power to use a considerable collection of books.” It was open seven days a week, until 9PM.

Children’s programming had been deemed important for a population among whom “the taste for good reading needed cultivation”, according to the 1905 Children’s Department report. While the Main Library displaced its newspaper room to the basement to make room for a children’s space, the Walnut Hills branch endeavored to keep up with its own large and noisy population of young patrons. It offered regular story hours and the popular stereo-opticon viewings. The librarians also saw the need to appeal to a population too old for story books and too young for adult topics, and began offering illustrated presentations on different countries, geography, history, civic duty, and opera. Specific teen programming didn’t appear in local libraries until the 1940s.

Some of the branch’s more traditional programming included preparing book lists for the local women’s reading clubs, but the new meeting rooms offered new uses for the community. UC Extension courses were held on topics like History and Astronomy. Musical recitals were a regular feature in the auditorium. Numerous other clubs met in the public rooms; groups such as the Alliance Française, City Beautiful, Classical Reading Club, College Club, Consumers League, Dramatic Club (Cincinnati Art School), Folklore Society, Mac Dowell Club, National Housewives’ Cooperation League, National Plant Fruit and Flower Guild, Nomad Club, and the Teachers’ Annuity Association. Prospective students and professionals took entrance exams in the auditorium, and the draft board set up shop during both World Wars. During periods of high unemployment, daytime use by men increased as they either looked for jobs, or used the space to pass time while not at work.

A perceived part of the librarians’ early 20th-century mission was to increase more “serious” use of the branch. Children’s programming sought to instill interest beyond story books and dime store literature, which was frowned upon. Branch librarians courted scholarly use via local institutions. They acquired reference works in History and Elocution for Walnut Hills High School students, and saw it as a point of pride when they could increase the reference collection at the branch. In 1919, they fulfilled reference work requests for more than 100 Lane Seminary research papers. Reading of novels beyond the classics was generally seen as frivolous entertainment, so nonfiction reading was highly encouraged,. Despite that effort, fiction remained among the most popular of the genres checked out.

Douglass Branch Library

From the collection of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County

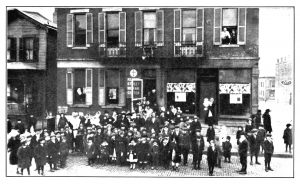

Amidst the construction of Hamilton County’s first six Carnegie buildings, other smaller branches either continued or began operation for different populations within the city. Home and school libraries borrowed a selection for a period of time before returning it for a new selection. In the midst of these options, in 1912, the Douglass Branch Library was opened in the new, state-of-the-art Frederick Douglass School building, less than ¼-mile away from the Walnut Hills Branch library. [We have published a separate post on this library.]

From the collection of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County

The Douglass School was established to serve the African-American community. The Douglass Branch Library began with 2,000 volumes, African-American librarian Lucille Pitts was at the helm, and two other staff: a substitute librarian and a high school page. It was open six days a week, from noon till 5, and 7 until 9:30 P.M.

According to the Public Library’s 1912 Annual Report, it was “justified in its existence, by the large settlement of colored people in the immediate neighborhood, which could not be cared for adequately at the larger branch.” It is not clear, in that report, what constituted that “adequate care”, nor whether members of the local African American community lobbied for a separate branch, or other forces were responsible for its opening. Nonetheless, the 1913 report stated that the North Cincinnati Branch (in Corryville) surpassed the Walnut Hills Branch in circulation numbers, for the first time, partly due to the latter losing patrons to Douglass.

During its existence, reports of special programming in that branch did not make it into PLCH print, and may not have existed via that institution. Douglass School, however, was a very active and beloved community hub that sponsored many public events. Some of our research has turned up ads in the African-American newspaper, The Union, for events such as bazaars, concerts, fashion shows and the like, put on by the school, itself, or by other organizations like the Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, and the local Republican Club, to name a few.

Only a few items about the Douglass Library were included in PLCH Annual Reports. In May 1913, librarian Lucille Pitts visited the Colored Branch of the Louisville Public Library. In the 1920s, enticing adult readers inside the Douglass Branch’s doors was perceived as an ongoing challenge, and downtown attitudes toward these patrons were not always favorable, as reflected in a 1923 report comment: “Adult use is not so satisfactory, and many do not yet appreciate the value of the Library.” As reported in our previous post, many adult patrons preferred to read books at Douglass over checking them out for home use, which might have otherwise added to circulation numbers.

In the 1930s branch librarians saw the effects of the Great Migration indicated by the following comment in the 1941 Ten Year Report: “The problem of service to the increasing number of Negro communities in both city and county is also before us. Walnut Hills north of McMillan Street and west of Victory Boulevard, together with the eastern edge of Avondale, has been almost completely taken over by Negro citizens. This large settlement depends for much of its service upon Douglass Branch, whose quarters in the Douglass School for Negroes have become altogether inadequate, even though some Negro readers use the Walnut HIlls Branch on the southern edge of their community.” The Douglass Branch closed in 1954. According to that year’s Annual Report, “slight use in recent years seemed to suggest that a separate agency within ½ mile of another larger branch was entirely unnecessary.”

Demographic Shifts

From Minogue, Anna C. The Story of the Santa Maria Institute. Cincinnati: Santa Maria Institute, 1922 .

The Walnut Hills Branch library experienced the tumults of the 20th century. Population shifts in the early suburbs — as well as changing attitudes –, were reflected in PLCH reports. The new residents were sometimes seen through differing lenses, depending on where they were from and the era. An influx of Italian immigrants in the 1920s was not served directly by the branch, but the Kenton St. Welfare Center staff served as a go-between, while new French and German immigrants, considered “men and women of culture and education who have come to our country for employment” and noted to “number among the most appreciative of our patrons,” were given “[a]s much individual attention … as is possible.”

“Members of Hengstenberg Lunch Table, 1884 ,Lunch Club,. Taken in a yard of residence of Mr. John V. Lewis, Grandview Ave., Walnut Hills, Cincinnati.” Credited to the Cincinnati Historical Society

About “…the great influx of mountain whites from Kentucky, Tennessee, and North Carolina, and of negroes from states even farther south”, the 1941 report noted, “we are losing our better type of readers.” By the 1950s, library reports expressed gratitude that its older branch libraries were so well used by this same population, particularly increasing the circulation of children’s books. Returned World War II Veterans, also, were celebrated as “earnest, hardworking, keenly appreciative, and [having] a definite goal.”

By the late 1950s, and into the early 60s, most of the main library’s attention was directed toward the new building, downtown, as well as the branch libraries being erected in the newer suburbs. Meanwhile, while Walnut Hills was not mentioned specifically, one inner ring librarian wrote, ‘There are several dynamics to consider in any attempt to understand this part of town. One is the exodus of long-time residents, another the influx of new families, usually of lower income. Urban Redevelopment has engendered a certain amount of anxiety among property-owners, but there are still the stand-patters who wish to remain in the neighborhood, come what may, regardless of block-busting and attempts of real-estate promoters to press them to sell.” These ongoing population shifts were the decided cause of “vacillating circulation” of books within these older branches. Annual reports, in these later eras are much less specific about the Walnut Hills Branch, so our research stops here, for now.

Today’s library is an important hub in the neighborhood, not to mention one of the few public commons remaining. It continues in this vein under the direction of today’s branch manager, Kendall Kidder-Goshorn, who has been collaborating with both Douglass and Spencer Schools to provide books to their libraries, and is also working with community partners to ensure its role in our neighborhood’s education campus is to provide a safe, wholesome space for the many children who spend their afternoons in this historic building. She has also worked hard to give accurate circulation and usage numbers to the Main Library as proof of its importance to our community. If you haven’t been to the Walnut Hills Branch, before, stop in to rub elbows with your neighbors, enjoy the architecture, meet the very friendly librarians, use the space (where quiet is respected), and pick up materials conveniently delivered from other libraries. Cincinnati has a nationally-recognized library system, and Walnut Hills plays a proud part. It will be among the first (along with Price Hill and Madisonville) in line for much-needed renovation (including handicapped accessibility) in the Public Library’s 10-year Facilities Master Plan. You can learn more about that, here:

https://www.cincinnatilibrary.org/branches/walnuthills.html

https://www.cincinnatilibrary.org/info/facilitiesmasterplan.html

Sue Plummer

Research about the library was done for a presentation to the Walnut Hills Historical Society on 11-15-17 at its monthly “On the Road” meeting held at the Walnut Hills Branch Public Library. Sources were, mainly, annual reports published by the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County, from 1901 – 1929, as well as Ten Year in Review reports for the 1930s and 1940s, and a few ads found in Wendell Dabney’s newspaper, The Union. There are some interesting parallels to how the branch is used in today’s Walnut Hills.

Other sources consulted:

- Armentrout, Mary Ellen. Carnegie Libraries of Ohio: Our Cultural Heritage. Wellington, Ohio: Armentrout. 2003.

- Fleischman, John. Free and Public: One Hundred and Fifty Years at the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County 1853-2003. Cincinnati: Orange Frazer Press. 2003.

- Ussery, Bernice. A History of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County, 1802-1961. for Leach, Prof. M.D. Library Science 521, Libraries and Librarianship, 7-31-1961.

- Tansy, Eira. “Branches from the Baron: Cincinnati’s Carnegie Libraries”, Ohio Valley History. Spring 2016, pps. 45-66.