Lane Theological Seminary on the east side Gilbert Avenue between Yale and Chapel was the first institution founded in Walnut Hills. It dated from about 1829 and enjoyed a very few years of explosive growth and building. Yet the first President, Lyman Beecher, led a “New School” of Presbyterians away from a larger “Old School” – predominant in Cincinnati – over what now seems a rather dry theological question about predestination and free will. Nor was Beecher’s schism the only controversy at the fragile little school for ministers. It was also famed for the “Lane Rebels,” Abolitionist students who left the seminary and Cincinnati just a years after they arrived, taking the most important funder’s money with them. Most historical interest in Lane Seminary fizzles out after recounting the momentous events of first three years or so. Nonetheless, Lane Seminary persisted for a century until it joined a larger institution in a forced merger early in the Great Depression.

Lane Theological Seminary on the east side Gilbert Avenue between Yale and Chapel was the first institution founded in Walnut Hills. It dated from about 1829 and enjoyed a very few years of explosive growth and building. Yet the first President, Lyman Beecher, led a “New School” of Presbyterians away from a larger “Old School” – predominant in Cincinnati – over what now seems a rather dry theological question about predestination and free will. Nor was Beecher’s schism the only controversy at the fragile little school for ministers. It was also famed for the “Lane Rebels,” Abolitionist students who left the seminary and Cincinnati just a years after they arrived, taking the most important funder’s money with them. Most historical interest in Lane Seminary fizzles out after recounting the momentous events of first three years or so. Nonetheless, Lane Seminary persisted for a century until it joined a larger institution in a forced merger early in the Great Depression.

In fact, Lane enjoyed a second era of prosperity during the years of Reconstruction after the Civil War. The New and Old Schools of Presbyterians, at least in the North, reconciled in 1869. (Northern and Southern Presbyterians would remain separate for another century.) With the merger of the factions, Lane finally merged its congregation with the old Walnut Hills Presbyterian founded by James Kemper. A grand new church building was built by the enlarged congregation without any seminary money. Lane found itself popular and prosperous; fundraising during the 1870s allowed the school to build a new seminary building including a teaching chapel, classrooms, and meeting rooms. Designed by Cincinnati architect James McLaughlin, the new main building was completed in 1880. Dormitory wings, including both a bedroom and a study for each occupant, followed the next year. Enrollment soared, and Lane attracted a faculty that rivaled the combination of Beecher and Stowe in the early years.

The late nineteenth century was an era of great missionary zeal. Of the eleven students who graduated from Lane in 1879, seven were already placed in foreign mission fields at the time of commencement. Asia became a favorite destination for the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions; many a young minister headed to China to convert the vast populace to Christianity. Alumni reunions sometimes included multiple missionaries with the same Chinese dialect conversing in their adopted language as comfortably as in English.

We have already seen that a small population of Chinese people migrating east from California from the mid-1870s settled in Cincinnati, mostly as washermen. What is perhaps more surprising, we find that a few of these immigrants came for ministerial education at Lane Seminary. Chin Gin and Huie Kim (often referred to with variant spellings) arrived in about 1880; the two well-educated men, fluent in English, had been converted and baptized in California and hoped to work themselves as missionaries. Various accounts suggested that one of them hoped to return to China, while the other planned to preach and convert Chinese residents in the US with his initial destination in Pennsylvania coal county.

These Chinese Seminarians played several import roles: they prepared to spread the Gospel to their countrymen; they preached in their own language at a Sunday School for around thirty potential or actual converts in Cincinnati; and they enriched the experience of their fellow Seminarians preparing for careers in an increasingly diverse world. Indeed, the little evidence I have turned up demonstrates that the Asian immigrants hoped as much as those from Europe for assimilation into American society. In the years before the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, at least one immigrant from that country became a naturalized American citizen and married a white woman in Cincinnati.

Chin Gin and Huie Kim charmed the Seminary and the other Presbyterians with whom they interacted. In February 1881 they arranged a Chinese New Year’s banquet, hosted by the Sunday School class, for the thirty or so American teachers for the class (which included volunteers offering instruction in English and basic arithmetic), and the Faculty of Lane Seminary. According to newspaper accounts, the Chinese hosts represented all but about 10 of their countrymen in the city. Quite a crowd gathered in May that year for their oral examinations, and all accounts marveled at their command of both the language and Biblical interpretation.

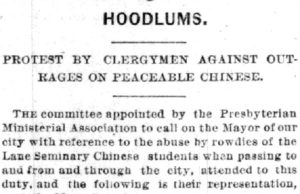

As “the Chinese Question” became a national political issue, the generally amused and dismissive attitude and minor harassment of the mid-1870s became more hostile and dangerous. In March of 1882 the faculty at Lane, supported by the Presbyterian Ministerial Association, complained to the mayor that “both the Chinese students in Lane Seminary have been knocked down and seriously injured by ruffians, and those young men can not pass from Walnut Hills to the city, on the Sabbath or any other day, without exposure to insult, often of the grossest kind.” The police had never come to the aid of the minority students, who reported that officers witnessed the attacks on more than one occasion. Appropriate inquiries were directed, but the Police Superintendent assured the mayor the police were alert to the needs of all residents and that the only specific instances of police-witnessed abuse came in either a more generalized riot or long ago on Gilbert Avenue, “where many good citizens besides our Chinese friends have been roughly used.” (White fragility may be a new phrase, but it is by no means a new phenomenon.)

As “the Chinese Question” became a national political issue, the generally amused and dismissive attitude and minor harassment of the mid-1870s became more hostile and dangerous. In March of 1882 the faculty at Lane, supported by the Presbyterian Ministerial Association, complained to the mayor that “both the Chinese students in Lane Seminary have been knocked down and seriously injured by ruffians, and those young men can not pass from Walnut Hills to the city, on the Sabbath or any other day, without exposure to insult, often of the grossest kind.” The police had never come to the aid of the minority students, who reported that officers witnessed the attacks on more than one occasion. Appropriate inquiries were directed, but the Police Superintendent assured the mayor the police were alert to the needs of all residents and that the only specific instances of police-witnessed abuse came in either a more generalized riot or long ago on Gilbert Avenue, “where many good citizens besides our Chinese friends have been roughly used.” (White fragility may be a new phrase, but it is by no means a new phenomenon.)

The US had entered into treaties with China to allow the immigration of labor to work on the Western Railroads, and to allow Christian missionaries to operate in China. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 abrogated most parts of the treaties granting rights to immigrants to the US; American missionary work nonetheless continued unabated in their country. The two, much abused, Chinese students remained on the Lane campus through the summer of 1882 – all the others took the hot months off – and it seems through the next academic year. A newspaper reported in September 1884, “Lane Seminary is flourishing with forty-six students. There are no Chinese students in the institution this year.”

References:

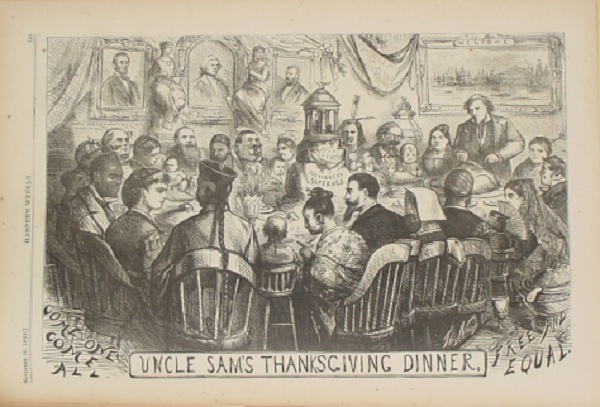

“Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving Dinner”, Harper’s Weekly, November 20, 1869

“Hoodlums,” Cincinnati Commercial Newspaper, March 11, 1882 Page 9

“The Chinese Sabbath School,” Cincinnati Daily Gazette Newspaper December 20, 1881 Page 10

“Thursday’s Storms,” Cincinnati Commercial Newspaper July 6, 1882 Page 8

“Lane Seminary is flourishing,” Cincinnati Commercial Gazette, September 27, 1884 Page 9

“Lane Seminary Commencement,” Cincinnati Commercial Newspaper May 5, 1881 Page 8

“Lane Seminary: Commencement Exercises,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 6, 1881

“Chinese New Year,” Cincinnati Commercial Newspaper February 15, 1881 Page 2

“Rev. Mr. Williams, one of the Alumni of Lane Seminary, who has been for twenty years a missionary in China,” Cincinnati Commercial Newspaper May 7, 1880 Page 10

More generally, see also “CHINESE IMMIGRANTS, CHINESE LABOR, COLUMBIA, IRISH AMERICANS, LABOR, MATERNAL SYMBOLISM, “THE CHINESE QUESTION” 1871, https://thomasnastcartoons.com/category/chinese-immigrants/

On Joe (or Jo) Sing, naturalized American citizen, and his marriage to a white woman,” Magistrates’ Courts,” Cincinnati Enquirer, 01 Apr 1879 Page 4 and “Samm and Sing” Cincinnati Commercial, October 28, 1876 Page 8