Lifting water requires a lot of work. An elevated reservoir stores both water and the work required to lift the water. The siting of the new reservoir in Walnut Hills provided not only lots of water, but lots of water pressure, for the city expanding up from the river front. (We shall see that settlement on top of the bluffs raised new problems for raising water, but that story can wait.) Moving millions of gallons of water up the two hundred feet or so from the river to the reservoir every day posed yet another engineering challenge for the Cincinnati Water Works during reconstruction.

Cincinnati was perhaps the first and largest industrial center in the age of steam. While we think of the railroad locomotive as the ultimate expression of steam power, even in transportation that’s jumping the gun. Steamboats – much larger and heavier than trains – required a lot more power, and Cincinnati was the center of steamboat building before the Civil War. The first steam pump for the waterworks in fact came out of a steamboat. A pair of engines built in the early 1850’s operated continuously until the Front Street station closed in 1907, but by the end of the Civil War they were barely adequate for the demand. Cincinnati’s leading steam engineer, George Shield, designed a new engine that went in to service in 1865. The Shield engine was the first of a long series of disappointments for the Water Works. It performed well short of its design capacity, and it proved both inefficient in its fuel consumption and temperamental in operation. (The engine ruined Shield’s reputation as an engineer and his business.)

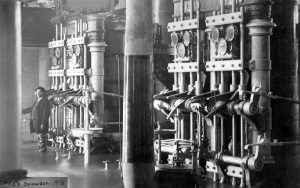

In 1871, Theodore Scowden, an antebellum director of the water works, returned to the position and designed an entirely new pumping plant, for which the city acquired land ten miles upriver from the city. The plans included two new steam pumping engines. Scowden estimated the cost at $4.5 million, which killed it before any work could begin. As the Eden Park Reservoir progressed and the output of the Shields engine did not, however, the Water Works determined to build the Scowden engines for installation at Front Street.

In 1871, Theodore Scowden, an antebellum director of the water works, returned to the position and designed an entirely new pumping plant, for which the city acquired land ten miles upriver from the city. The plans included two new steam pumping engines. Scowden estimated the cost at $4.5 million, which killed it before any work could begin. As the Eden Park Reservoir progressed and the output of the Shields engine did not, however, the Water Works determined to build the Scowden engines for installation at Front Street.

Scowden’s estimate for the materials for the pumps came to 800 tons of iron, to be completed in about 5 months. The Water Works contracted with a company controlled by Charles and John Kilgour to fabricate the equipment for a little under $100,000. The newspaper accounts are difficult to piece together, but the Kilgours emerge universally as villains. The final contract, signed by the Water Works engineer Earnshaw, failed to specify a time frame for the construction. The Kilgours took their time, and they made the engine a great deal beefier than specified. The amount of iron ballooned to more than a thousand tons, and the Kilgours asked to be compensated for the overage by the pound. The Water Works, stuck with a poorly written contract, decided to avoid litigation. The Kilgours took the money and turned the unfinished machinery over to Scowden who hired his own crews to complete the fabrication.

Despite the expense and the delays and the resentments, Scowden’s engines performed admirably from the time of their first test in 1874 through the shut-down of the plant in 1907. They delivered water to the initially leaky reservoir, and finally went into continuous production in 1875 with the completion of the upper basin, which was joined in 1878 by the completed lower basin of the reservoir. For the initial tests, the engines ran powered by steam from the boilers already on site to run the existing engines; before the system could run permanently, the Front Street facility required two new boilers to power the Scowden engines.

References:

For general references, see the first article in this series, Construction during Reconstruction: Eden Park Reservoir Walls

The illustration comes from the excellent history site of the Cincinnati Water Works. http://cincinnatitriplesteam.org/ and https://www.cincinnati-oh.gov/water/about/gcww-history/

On the Kilgour contract and delays on the delivery of the pump engine, see The Cincinnati Enquirer (Cincinnati, Ohio), 25 Jul 1873, Page 4; The Cincinnati Enquirer (Cincinnati, Ohio), 27 Sep 1873, Page 2; The Cincinnati Enquirer (Cincinnati, Ohio), 07 Oct 1873, Page 2; The Cincinnati Enquirer (Cincinnati, Ohio), 10 Oct 1873, Page 8; The Cincinnati Daily Star (Cincinnati, Ohio), 25 Jun 1875, Page 4

A similar dispute occurred between Charles Kilgour and the Newport, Kentucky Water Works concerning a pump engines in 1874: The Cincinnati Enquirer (Cincinnati, Ohio), 02 Feb 1874, Page 8; The Cincinnati Enquirer (Cincinnati, Ohio), 28 Apr 1874, Page 8

On Shield and his engine, see Cincinnati City Water Works Report for 1861, p. 231; Chicago Tribune (Chicago, Illinois), 25 Jul 1872, Page 4

On Scowden and his engines, see references to the Kilgour contracts; the engines were designed by Scowden. See also The Cincinnati Enquirer (Cincinnati, Ohio), 02 Feb 1874, Page 8; City Water Works Report 1879, p. 417. An uncritical biographical sketch appears in James Landy, Cincinnati past and present, or, Its industrial history as exhibited in the life-labors of its leading men (Elm Street Printing Company, Cincinnati, 1872) pp. 373-377