Since the nineteenth century, the Cincinnati Public Library provided service in the district’s school buildings. Douglass was no different; it housed a small library for the use of its students. Through the end of the nineteenth century, most adult library services required a trip to the main library building downtown. Andrew Carnegie, the iron baron and one of the richest men of his times, set out in the early years of the twentieth century to build libraries for communities that would support them. In Cincinnati, the very first branch library was built in Walnut Hills in 1906; that library still serves the community on Kemper Lane at William Howard Taft Road.

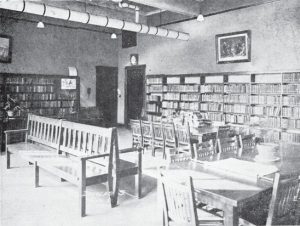

When Cincinnati Public Schools built a new Frederick Douglass School building in 1911, it included a large library room on the first floor. It was especially built to accommodate adult patrons in the evenings. It had a separate street entrance, so the library could be open when the school building was otherwise closed. In 1912, the Public Library hired a new librarian, Lucille Pitts, to staff the special school branch. Miss Pitts “entered by competitive examination,” apparently the first African-American librarian in the Cincinnati system. She lived on Ashland Avenue, close to the old Walnut Hills High School and just a few blocks from Douglass. She was “given a special apprentice course” and had the assistance of a high-school page and a substitute librarian. The facility was open to adults from the community from noon to five and seven to nine-thirty. Adult circulation was low, although this was in part because “many of them would prefer reading in the pleasant library room to drawing books for home use.” Miss Pitts stayed at the library into 1917. The segregated Douglass School library remained open for decades.

When Cincinnati Public Schools built a new Frederick Douglass School building in 1911, it included a large library room on the first floor. It was especially built to accommodate adult patrons in the evenings. It had a separate street entrance, so the library could be open when the school building was otherwise closed. In 1912, the Public Library hired a new librarian, Lucille Pitts, to staff the special school branch. Miss Pitts “entered by competitive examination,” apparently the first African-American librarian in the Cincinnati system. She lived on Ashland Avenue, close to the old Walnut Hills High School and just a few blocks from Douglass. She was “given a special apprentice course” and had the assistance of a high-school page and a substitute librarian. The facility was open to adults from the community from noon to five and seven to nine-thirty. Adult circulation was low, although this was in part because “many of them would prefer reading in the pleasant library room to drawing books for home use.” Miss Pitts stayed at the library into 1917. The segregated Douglass School library remained open for decades.

In 1920, a commemorative publication for Frederick Douglass School noted that the library was a branch of the Cincinnati Public Library and helped “foster the reading habit among the children and throughout the community.” The annual circulation stood at about 12,000 volumes, roughly a tenth of the circulation from the much larger Walnut Hills branch. It served 230 new members that year, with an average daily attendance of between 350 and 400 adults and children.

James Robinson, a Douglass teacher from 1915-1918 and later Executive Secretary of the Negro Civic Welfare Committee of Cincinnati’s Council of Social Agencies observed in 1920, “The library, evening schools and community meetings afford opportunity for the older people to improve themselves and to give free play to ideas and instincts which wou1d otherwise stifle and die for want of expression. Certainly the colored section and the larger cosmopolitan area owe much to the presence of Douglass School.”

Geoff Sutton

See also our page on the Walnut Hills Branch Library which opened in 1906, just a half-mile away but largely for white patrons.