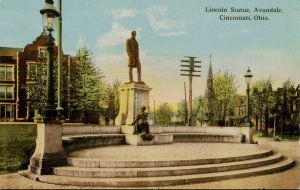

Venturing on a walk from Walnut Hills to our neighbors in Avondale, I passed the Abraham Lincoln Memorial at the corner of Rockdale and Reading, outside South Avondale School. The scene was colorful, solemn, appropriate, and extremely moving to me. A monument and a corner that has seen much controversy over the years, it has raised and dashed many dreams since Decoration Day in 1902 – what we now call Memorial Day – when the monument disappointed by not being finished for its scheduled dedication. At the foot of the Lincoln statue, at a level where all of us may join her, sits a second bronze figure, depicting Lady Liberty with her quill outstretched.

Venturing on a walk from Walnut Hills to our neighbors in Avondale, I passed the Abraham Lincoln Memorial at the corner of Rockdale and Reading, outside South Avondale School. The scene was colorful, solemn, appropriate, and extremely moving to me. A monument and a corner that has seen much controversy over the years, it has raised and dashed many dreams since Decoration Day in 1902 – what we now call Memorial Day – when the monument disappointed by not being finished for its scheduled dedication. At the foot of the Lincoln statue, at a level where all of us may join her, sits a second bronze figure, depicting Lady Liberty with her quill outstretched.The decorations of our day in the photograph say that the current generation in Avondale, with the children of its resegregated school, have seized that freedom pen to cry out that Black Lives Matter, that we need to name those whose lives mattered so little that to the police they were extinguished. What is striking to me is that the protest decorations are so fitting to the monument. They bring an urgency to the old symbol of those who would petition their government. The phrases presently covering the pedestal are new: “I can’t breathe”; “Serve and protect, not abuse and neglect”; “No justice, no peace”. The larger story, however, is the same as it was when the Monument was erected and dedicated in late 1902. At that time, Ida B. Wells and other African American journalists had begun to document the Southern barbarity of Lynching – work still sufficiently imminent that the National Memorial for Peace and Justice memorializing 4,400 victims opened just a few years ago. In our own time the identity of those who murder unarmed Black men are too often police officers.

The pedestal on which the Avondale Lincoln statue stands bears the inscription “With malice toward none,” a phrase from Lincoln’s second inaugural. Lincoln’s short address ended anticipating the conclusion of the Civil War and looked ahead to Reconstruction, the reintegration of the Confederate states with their large populations of Freemen into the Union. Ever since the surrender of the Confederacy there have been conflicting interpretations of Lincoln’s meaning: African Americans and their allies have taken the martyred president to mean equality for Black Americans, while former Confederates and their allies have claimed the phrase as protection for themselves. In 1902, when the Avondale monument was constructed, the movement (most strongly associated with the Daughters of the Confederacy) to created memorials for soldiers who joined the Rebellion was just coming into its own. It is finally time to say that such memorials have no place in our new century.

The pedestal on which the Avondale Lincoln statue stands bears the inscription “With malice toward none,” a phrase from Lincoln’s second inaugural. Lincoln’s short address ended anticipating the conclusion of the Civil War and looked ahead to Reconstruction, the reintegration of the Confederate states with their large populations of Freemen into the Union. Ever since the surrender of the Confederacy there have been conflicting interpretations of Lincoln’s meaning: African Americans and their allies have taken the martyred president to mean equality for Black Americans, while former Confederates and their allies have claimed the phrase as protection for themselves. In 1902, when the Avondale monument was constructed, the movement (most strongly associated with the Daughters of the Confederacy) to created memorials for soldiers who joined the Rebellion was just coming into its own. It is finally time to say that such memorials have no place in our new century. The Lincoln Monument came to Avondale with good abolitionist credentials. A wealthy Civil War veteran named Charles Clinton who retired to Cincinnati came across the pair of bronzes in Philadelphia in 1900. He purchased them and had them shipped to his adopted city. He offered to donate them for installation if someone would provide a suitable location and foundation. There were no immediate takers; the one-time mayor of the formerly independent village of Avondale suggested the annexed neighborhood as a site. Difficult negotiations with the donor finally led to the grounds of the Avondale School. An “elaborate program” was arranged for Lincoln’s Birthday, February 12, 1902, at the Avondale Presbyterian Church, including an invocation by a Rabbi and a speech by Cincinnati Mayor Julius Fleishmann, himself an Avondale resident. Funding (including donations from Avondale school children) was secured. A plan for the pedestal and spacious granite bench was contracted, but the Boston stone subcontractor failed to deliver and the scheduled Memorial Day opening was postponed until December.

The Lincoln Monument came to Avondale with good abolitionist credentials. A wealthy Civil War veteran named Charles Clinton who retired to Cincinnati came across the pair of bronzes in Philadelphia in 1900. He purchased them and had them shipped to his adopted city. He offered to donate them for installation if someone would provide a suitable location and foundation. There were no immediate takers; the one-time mayor of the formerly independent village of Avondale suggested the annexed neighborhood as a site. Difficult negotiations with the donor finally led to the grounds of the Avondale School. An “elaborate program” was arranged for Lincoln’s Birthday, February 12, 1902, at the Avondale Presbyterian Church, including an invocation by a Rabbi and a speech by Cincinnati Mayor Julius Fleishmann, himself an Avondale resident. Funding (including donations from Avondale school children) was secured. A plan for the pedestal and spacious granite bench was contracted, but the Boston stone subcontractor failed to deliver and the scheduled Memorial Day opening was postponed until December.– Geoff Sutton