Robert Gordon, a Black man who lived in Cincinnati from about 1847 through his death in 1884, makes occasional appearances in obscure historical accounts of nineteenth-century Cincinnati. He pops up in popular press accounts as a former slave who made a fortune in the coal business. Yet it turns out that Gordon left a considerable documentary trail in Cincinnati that allows a more subtle understanding of the man and his family and businesses.

Gordon’s origin story is a common one for free Blacks in Cincinnati. He began his life enslaved. His master, described as a Virginia coal merchant and a yachtsman, put Gordon in charge of the coal yard. He allowed the slave to have the “slack” – the coal dust that covered everything in the yard. Gordon managed to make the slack useful to industrial customers. There is no evidence how he processed and marketed the waste dust; if the process were obvious or simple it certainly would have been exploited by owners in a slave economy. He sold his product and saved, he bargained with his master to buy his freedom in 1846, and he set off for the free states.

Gordon found his way to Cincinnati. Most accounts say he arrived in 1847, although I have discovered no documentary evidence about him in the city until the next year. (To be sure, a transient freeman would be unlikely to leave much official trace.) On November 1, 1848 he paid the considerable sum of $2000 for property on the Miami Canal at Eighth and Lock Streets. It seems Gordon established his residence and a business office there. On September 1849, Gordon married Eliza Jane Cressup. Not all the blanks on the recorded copy of marriage license record are filled in: Robert’s first name is recorded only with a squiggle, there is no notation even that both spouses were of legal age, and the name of the officiant is even more abbreviated than Gordon’s. Several other records in the same book omit similar information; it is likely that the copyist couldn’t make them out in the originals.

The 1850 census provides benchmark information on Robert Gordon’s presence in Cincinnati. The census form for the First Ward (which included the area on Eighth Street near the Canal) shows the household consisting of just Robert and Eliza. She was at that time 25 years old; her birthplace listed as Ohio, so she was free born. Robert set his age as 38, indicating he had arrived in Cincinnati in his mid-thirties. The box for value of real estate showed $2500; perhaps Gordon or the census-taker thought his house had appreciated, perhaps he had improved the property or made another small investment elsewhere. Already, in short, the Gordons enjoyed a comfortable middle-class existence by any standards, complete with a single-family home.

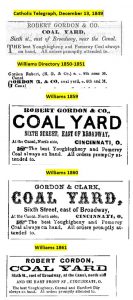

At about the same time as his marriage in the fall of 1849, Gordon set himself up as a coal dealer. The 1850 census confirms that occupation. The first advertisement for his business I have found appeared regularly in the weekly Catholic Telegraph newspaper beginning in late 1849 as “Robert Gordon & Co. Coal Yard, Sixth St., east of Broadway, near the Canal.” The business was two blocks south of his home. It was on the same side of the same block, at least, as the shop of the Black carpenter Thomas Crissup – whose name was spelled many different ways including Cressup. It seems likely that Gordon’s business was next to his father-in-law’s. Later real estate transactions indicate that Gordon assumed a lease on the coal yard property in October 1850.

The business progressed. In 1853 Gordon purchased the lot he had leased in 1850 – officially at Sixth and Culvert, for $2,250. The 1860 census increased the value of his real estate to $4000. It is worth noting that the documented purchase prices of two properties at Sixth and Eighth on the Canal totaled $4200; the $2500 valuation in the 1850 census and the $2250 purchase in 1853 totaled closer to $5000 than $4000. For whatever reason, Gordon apparently undervalued his real estate for the Census-taker.

From the late 1840’s onward, the annual Williams Directory was the standard reference for personal and business names and addresses in Cincinnati. Robert Gordon’s first listings in the directory appear in the volume for 1850-1851: there is a personal entry at the Eighth Street property on the Canal, followed by a bold-faced business entry for the coal yard on the Canal at Sixth. The same directory further included a mention in the business category for “Coal Yards” – his was one of only a dozen listed. Scanning the directory for coal dealers turns up dozens more who did not opt for the category listing, indicating Gordon was a substantial and sophisticated business owner. Yet Gordon did not choose the most extravagant option: four yards on the Williams list had notation referring in addition to display ads; the yard on Sixth Street was not among them.

From the late 1840’s onward, the annual Williams Directory was the standard reference for personal and business names and addresses in Cincinnati. Robert Gordon’s first listings in the directory appear in the volume for 1850-1851: there is a personal entry at the Eighth Street property on the Canal, followed by a bold-faced business entry for the coal yard on the Canal at Sixth. The same directory further included a mention in the business category for “Coal Yards” – his was one of only a dozen listed. Scanning the directory for coal dealers turns up dozens more who did not opt for the category listing, indicating Gordon was a substantial and sophisticated business owner. Yet Gordon did not choose the most extravagant option: four yards on the Williams list had notation referring in addition to display ads; the yard on Sixth Street was not among them.

Beginning in 1861 the Williams Directory began to show a new address for Gordon & Co., with yards on the Canal not only at Sixth but also at Front Street – right on the river. Presumably Gordon purchased coal there by the barge load. The property at Eighth Street was listed as simply his home address, “10 Eighth Street Hill.” During this period of business expansion his footprint in the Williams Directory grew as well, although several other dealers consistently purchased a larger directory presence. In 1858 Gordon opted for a more prominent listing in the Coal Yards business category; the next year he bought his first display ad.

The consistent use of “& Co.” for Gordon’s yard coal directories and advertisements point to a collaborator. Partnership is confirmed in a mention in William Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator magazine and reprinted in the Anti-Slavery Bugle in December 1856: a letter from Cincinnati describing Black businesses in the city noted (along with Henry Boyd’s bedstead factory, James Presley Ball’s Daguerreotype Saloon and Robert Duncanson’s painting studio) “two colored men are the proprietors of a large coal yard.”

In 1860 Gordon’s Williams Directory alphabetical listings remained the same, but his display ad (that year only) read “Gordon and Clark Coal Yard.” Presumably Mr. Clark was at least part of “& Co” in earlier listings. Yet in 1861, the first year Gordon advertised both yards on the canal at Sixth and at Front, the company name reverted to “Gordon and Co.”

Gordon continued in the coal business into 1865, when he was in his mid-fifties. At the close of the Civil War, however, he retired, moved to Walnut Hills, and transferred most of his investments to real estate. We shall return in a later post to the history, or the historiography, of Gordon’s coal business as told in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. For the present, however, the most striking thing about Gordon & Co. was that it thrived for nearly twenty years, growing organically from small beginnings to larger premises and prominence, and passed to Black successors.

Robert Gordon, resident east of Sixth and Broadway

Robert Gordon, an African American who bought his freedom from enslavement in 1846, ran a successful coal business from 1849-1865, and a successful real estate and development business from 1865 until his death in 1884. Historical accounts through many generations have treated these enterprises as isolated individual achievements, the triumph of a single Black man over the opposition of the white community. Like all Black Cincinnatians, Gordon of course faced adversity and opposition from the white power structure. His path to success, however, came in the context of a long-standing and thriving Black community; in his later career he nurtured and cultivated that community. His long life, often cast as an isolated exception, in fact represented an outstanding example of Black excellence.

To begin with the personal, he married into an established Cincinnati family. Gordon’s wife Eliza Jane Cressup was the daughter of a Black carpenter named Thomas Crissup who first appeared in the 1820 census of Cincinnati. The 1840 census enumeration for Thomas’ household included three unnamed “free colored women” in Eliza’s age range. The 1850 census, after the Gordons’ wedding in 1849, (which for the first time listed dependents by name and spelled the surname “Cressup”) found only two daughters. When Gordon married Eliza Jane, he married into the Black aristocracy.

The African American community had been threatened with expulsion from Cincinnati in 1829 through draconian enforcement of the Ohio Black Laws. Thomas Crissup went to Canada that year as a representative of his race and negotiated the purchase of land for the proposed village of Wilberforce, Ontario. The plan for emigration did not satisfy white Cincinnati; riots ensued inflicting injury and damage on the Black neighborhood. After the Wilberforce purchase, Crissup (like most Black Cincinnatians) rejected the plan for self-deportation, and he returned to Cincinnati. Beginning in 1831 he appears regularly in city directories, consistently as a carpenter, and consistently on Sixth Street with the description of the block as varied as the spelling of his last name: near Deer Creek, east of Broadway, near the Canal, near Culvert Street and so on. The location didn’t change, just the names and significance of the surrounding landmarks. Thomas Crissup was an anchor.

Gordon’s coal yard lay on the same side of the same block as Thomas Crissup’s carpenter shop. Also on Sixth Street in the small space between Broadway and the Canal, we find the home of John Isom Gaines, a Black stevedore turned grocer, with wealth comparable to Gordon’s. Gaines chaired the board of the Colored Schools in Cincinnati during a sort of false start in 1849, and again in the later 1850’s. He also represented the city at many Colored Conventions. Henry Boyd, famous as a manufacturer of furniture (especially bedsteads), had his factory on Broadway at Eight Street (within a block or two of Gordon’s Eight Street residence) and his home on New street, between Sixth and Seventh just west of Broadway. Boyd, at the center of underground railroad activity in Cincinnati in the 1840’s and ‘50’s, owned real estate valued at $20,000 in 1850 census. He served with Gaines on the Colored School Board in 1855-56. A steamboat steward named Samuel Wilcox opened a grocery at Fifth and Broadway in about 1850. He, like Gaines, specialized in fancy goods for the steamboat trade as well as the local market. Wilcox thrived for six years before failing, owing (Black sources are universal in declaring) to extravagant living and immorality.

Gordon’s coal yard lay on the same side of the same block as Thomas Crissup’s carpenter shop. Also on Sixth Street in the small space between Broadway and the Canal, we find the home of John Isom Gaines, a Black stevedore turned grocer, with wealth comparable to Gordon’s. Gaines chaired the board of the Colored Schools in Cincinnati during a sort of false start in 1849, and again in the later 1850’s. He also represented the city at many Colored Conventions. Henry Boyd, famous as a manufacturer of furniture (especially bedsteads), had his factory on Broadway at Eight Street (within a block or two of Gordon’s Eight Street residence) and his home on New street, between Sixth and Seventh just west of Broadway. Boyd, at the center of underground railroad activity in Cincinnati in the 1840’s and ‘50’s, owned real estate valued at $20,000 in 1850 census. He served with Gaines on the Colored School Board in 1855-56. A steamboat steward named Samuel Wilcox opened a grocery at Fifth and Broadway in about 1850. He, like Gaines, specialized in fancy goods for the steamboat trade as well as the local market. Wilcox thrived for six years before failing, owing (Black sources are universal in declaring) to extravagant living and immorality.

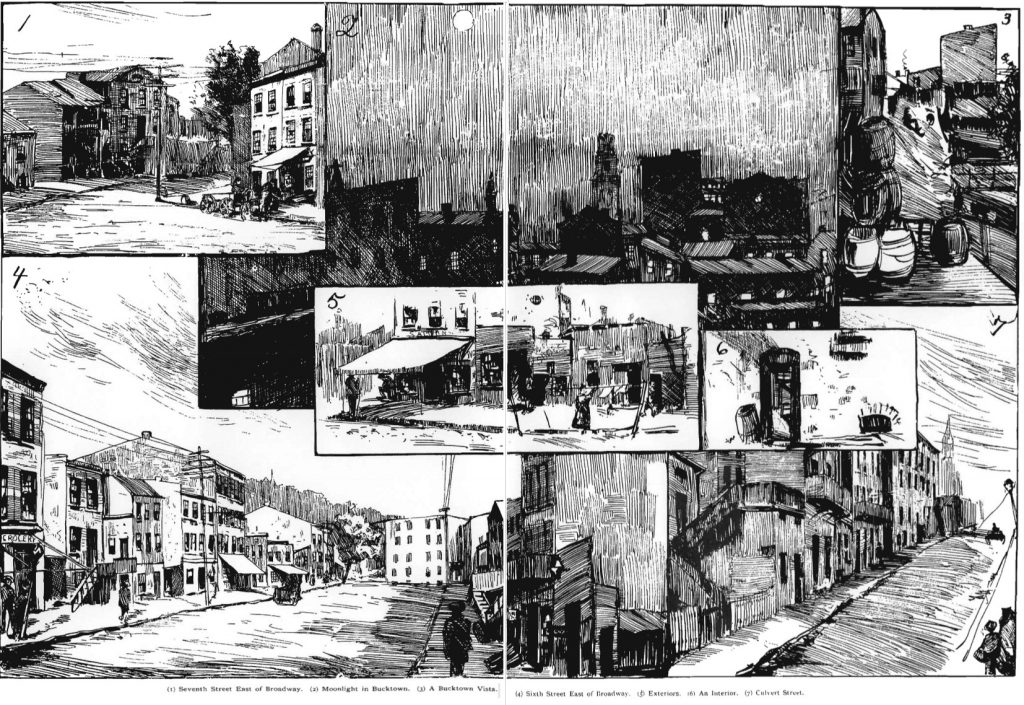

Bucktown, in Wards 1 and 13. Detail from map, frontispiece, Williams Directory 1855

In more expansive terms, Robert Gordon established his home and his coal yard in the geographical heart of the Black community in the neighborhood would become known as Bucktown. African Americans in the mid-nineteenth century were never a majority there or anywhere else. When Gordon established himself in the area it was a solid sort of place with many middle-class families, both Black and white. The center of the community sat at Sixth and Broadway. In 1824 that had become the location of a Black Church (Allen AME) and also, a decade later, of a Jewish Synagogue – each the first worship space of its kind west of the Alleghenies. Extending in and around the rough triangle bounded by Broadway and the Miami Canal from about Fourth to Eighth Streets, during the 1820’s through the beginning of the Civil War this was the favored neighborhood for successful Black businessmen. The 1843 city directory listed more than 35 Colored residents, with their occupations, on Sixth Street east of Broadway alone; many more lived nearby on Seventh Street, Eighth Street or just west of Broadway on McAlister and New.

Robert Harlan, a light-skinned Black from a wealthy Kentucky household had made a fortune running a store in California early in the Gold Rush; he moved to Cincinnati and built a large stone house on Fifth Street east of Broadway in 1851. The Dumas House Hotel, perhaps owned by Harlan, lay between Fourth and Fifth Streets, east of Broadway on a sort of overgrown alley called McAlister Street. It was reputed to have ties to the Underground Railroad. The Dumas was the only hotel in town that served Black guests. Some were free; some were fugitives; some, ironically, were enslaved domestic servants of visiting Southern businessmen. The Dumas was also where the so-called riots of 1841 began, in which armed white mobs again attacked the African American community – only to be repulsed in a pitched battle.

Bucktown not only served as the location for residences, businesses, and institutions in the Black community. It was the place of its soul – the center of cultural demonstrations. On August 1, 1855 a festival celebrating the anniversary of the emancipation of slaves in the British Caribbean began with speeches, and songs by a sixty-voice interracial girls’ choir at the Sixth and Broadway. This served as a sendoff for a march including a Black band and several Black civic organizations. Following the Canal to the river, they all made their way onto an awaiting steamboat for a cruise. African Americans could manage spectacle as well as the Germans or the Irish.

Now a broad expanse of surface parking lots beneath a tangle of highway overpasses just east of the Proctor and Gamble headquarters, Bucktown was in fact quite accommodating to its business residents. It boasted ready access to the southernmost leg of the Miami Canal. Opened in 1829, the long ditch enjoyed its greatest commercial success before serious competition from the railroads in the 1850’s. The lower section only was turned into a storm sewer and covered by Eggleston Avenue in 1870, making it attractive to the railroad. Gordon’s coal yard until that time had been an obvious beneficiary of cheap transportation by water, like the Alms and Doepke department store and warehouse a few blocks north on the Canal at Sycamore. In the 1880’s, white descriptions of Cincinnati began to cast Bucktown as a neighborhood of violence, poverty, prostitution and crime. Perhaps that was what the white community went there for. More likely, the depiction had its roots in the propaganda of the Cincinnati, Lebanon and Northern railroad that hoped to move its terminal from Court Street to Fountain Square by laying rails through the neighborhood to Fifth Street.

In this august antebellum company, Gordon did not leave significant individual biographical details. He did not apparently emerge as a leader in the Abolition movement, in the Black churches or schools, or in any way that gained notice in the white press. His profile would rise dramatically as he worked in Walnut Hills during Reconstruction.

Walnut Hills Real Estate

Robert Gordon ran a successful, growing coal business along the lower Miami Canal (later Eggleston Avenue) from 1848-1865. After the Civil War he retired, moved to Walnut Hills, and invested in real estate. By the time of his death in 1884 he was recognized as the wealthiest Black man in the state of Ohio, leaving his wife and daughter an estate of about $200,000.

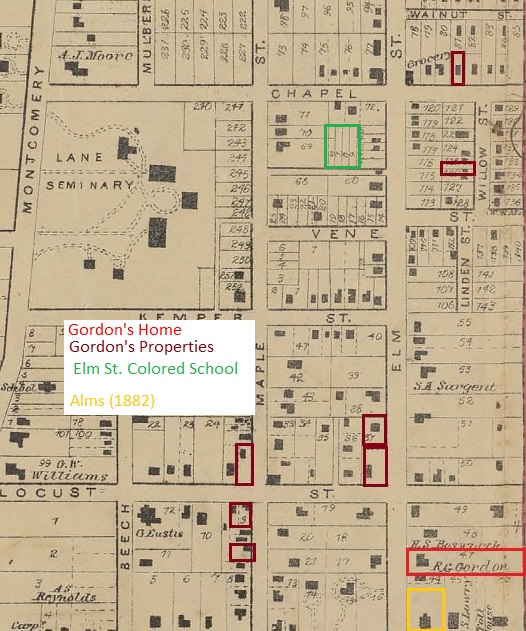

Cincinnati’s city limit through the Civil War ran along what is now McMillan Street. A hundred acres of the land north of McMillan and east of present-day Gilbert Avenue (the “Northeast Quadrant” of Walnut Hills) had been donated or sold to the Lane Theological Seminary around 1830. The campus proper occupied the block east of what is now Gilbert Avenue between Chapel Street and Yale. The institution had a brilliant start that turned out to be a flash in the pan. Internal divisions among the Presbyterians concerning slavery, an economic depression caused by President Andrew Jackson’s destruction of the Second Bank of the United States, and alienation of the Cincinnati business community caused by the students’ embrace of abolition left the institution is financial shambles. Beginning in 1843, Lane subdivided its land, beginning with plots between McMillan and Locust (now William Howard Taft). Early on many of the buyers, like Calvin and Harriet Beecher Stowe, were connected with the seminary.

In order to raise money, Lane generally granted ground leases for ninety-nine years, allowing the lessee to occupy and improve the property but requiring an annual rent payment to the Seminary. The institution imposed some limitations on the lessees, for example forbidding liquor stores. This system has complicated real estate in the neighborhood to the present day; many properties have separate owners for the land and the buildings on the land.

Even before the Civil War a small cluster of African Americans lived in Walnut Hills. There were enough families on Willow Street (now the north block of Preston) and Kemper Street (now Yale) to form a small house church in the mid 1850’s. There are a number of stories of African-American servants serving the ante-bellum Lane Seminary community as well.

Only after the Civil War did housing expand enough to support a significant population. Robert Gordon, the wealthy Black coal merchant, was among the first businessmen to buy a house on the on the old, extended Lane Seminary grounds. His large residence occupied a lot on the east side Elm Street (later Alms Place and now Victory Parkway) between McMillan and Locust (present-day Taft). The lot is currently occupied by the Maronite Catholic Church. For geographical and social reference, fifteen years later the dry goods merchant Frederick Alms would buy a house at the south end of the same block.

Gordon’s real estate dealings established Walnut Hills during Reconstruction as the premiere suburb for middle-class African Americans in Cincinnati. Within a few years, Gordon began to acquire and develop a large number of lots and buildings, mostly in the Lane Seminary subdivision, but also in other parts of Walnut Hills. Certainly, his choices were partly just a matter of timing: Cincinnati grew during the Civil War and reconstruction; Walnut Hills was the closest suburb with at least rudimentary transportation infrastructure, and Gordon had a considerable fortune to invest. Lane Seminary’s financial embarrassment, coupled with a decision by treasurer Joseph Glass Monfort to concentrate the institution’s endowment in real estate, allowed organized, planned residential development. (Monfort himself bought the house originally built for the President of Lane, now known as the Harriet Beecher Stowe House, at what is now Gilbert at Foraker.) A researcher more skilled in property documents than I could paint a much fuller picture of Gordon’s development, but his strategy was a simple one, parallel to Monfort’s for Lane: buy and hold, generating income from rentals.

Gordon began his acquisitions no later than 1865: that year, he purchased a lot on the west side of Maple (now Park) in the block north of McMillan. In 1866 he bought another house half a block north, at the corner of Locust (now Taft). Another transaction indexed the same year, but missing from the Deed book, may have been on Willow. In 1868 Gordon spent more than $12,000 on two properties downtown. In 1869 he returned to Walnut Hills investments, paying $9000 for property south of McMillan, on the west side of Kemper Lane, north and south of Curtis. (Both streets continue to bear those names today.) This was more or less across the street from the white Walnut Hills Methodist Church (later the white Baptist Church) and the Episcopal Church of the Advent. Later in the year he purchased three more properties in the Lane Seminary subdivision for a total of a little more than $14,000. The Census for 1870 valued Robert Gordon’s real estate holdings at $40,000 – as in 1860, somewhat undervaluing the purchase prices paid. He also declared other assets of $20,000.

In 1870, Walnut Hills agreed to annexation by the city of Cincinnati. Though his Walnut Hills properties now all fell within the city limits, the was little practical effect. More unusually, in 1873, Gordon took the step of purchasing the land for eight lots of Lane Seminary property for $1,263.67. He already owned the buildings on those lots; he bought out the leases on the land. The country had entered a recession. It is not clear what combination of financial difficulties for Lane, business caution on Gordon’s part, or relations between the Black landlord and Lane’s treasurer J. G. Monfort might have inspired this deal. Whatever the reasoning, the transaction at the beginning of Grant’s second term and the height of Reconstruction spared Gordon and his tenants from any restrictive covenants the Presbyterians might have later imposed on the neighborhood.

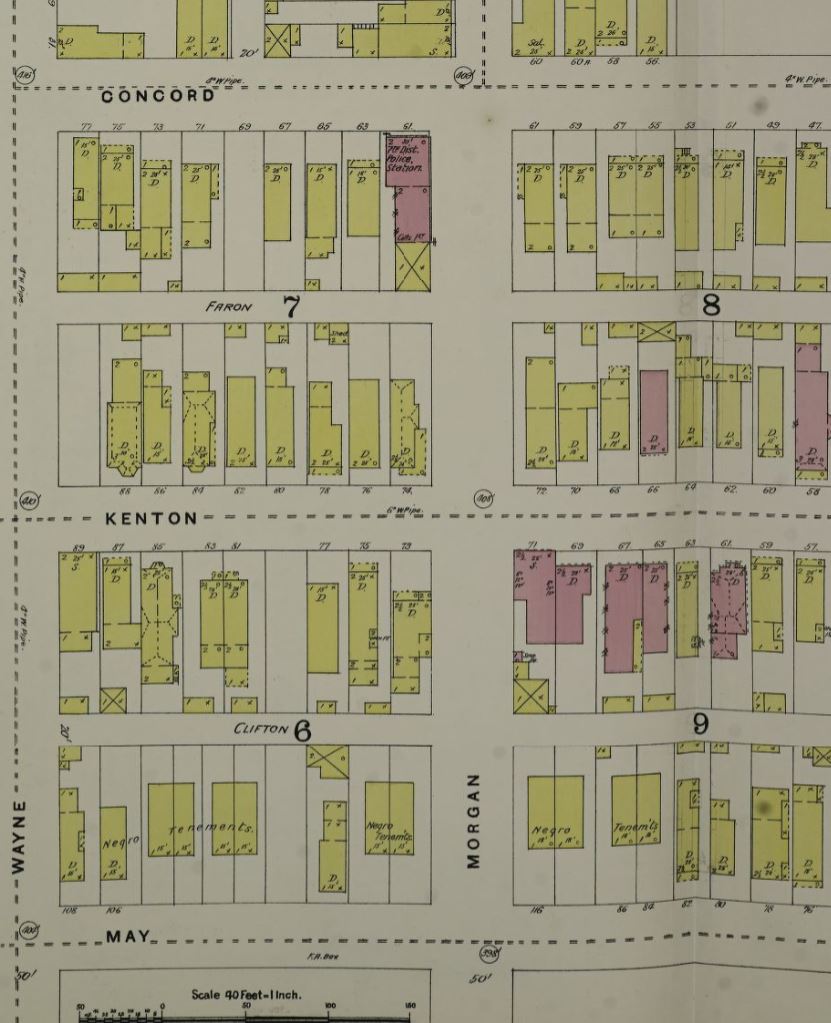

Gordon operated as a developer of property as well as a buyer and owner. Here the annexation of Walnut Hills had more importance. In 1871, Gordon was able to fill an order for nearly $2000 worth of bricks for the Elm Street Colored School, as well as a smaller contract to drain the lot. Gordon’s was the largest invoice for the school, apart from the $3,700 lot. Information about building projects is harder to come by than land transactions, but in 1878 Gordon built a two-story brick building at Kenton and Morgan. This project was an early one in the “southwest quadrant” – south of McMillan and west of Gilbert. Gordon’s building seems to have an important effect in the area: the 1891 Sanborn Fire Insurance maps show several “Negro Tenements” nearby, especially on May Street. Like the consolidation of the northeast quadrant as an area of African American building ownership and residence in the late 1860’s, the establishment of the southwest quadrant as a residential area for Black industrial workers along the Reading Road and Railroad corridor along the western border of the neighborhood owed a great deal to Gordon’s vision for his community during the age of what WEB Dubois would later dub “Black Reconstruction.”

Gordon operated as a developer of property as well as a buyer and owner. Here the annexation of Walnut Hills had more importance. In 1871, Gordon was able to fill an order for nearly $2000 worth of bricks for the Elm Street Colored School, as well as a smaller contract to drain the lot. Gordon’s was the largest invoice for the school, apart from the $3,700 lot. Information about building projects is harder to come by than land transactions, but in 1878 Gordon built a two-story brick building at Kenton and Morgan. This project was an early one in the “southwest quadrant” – south of McMillan and west of Gilbert. Gordon’s building seems to have an important effect in the area: the 1891 Sanborn Fire Insurance maps show several “Negro Tenements” nearby, especially on May Street. Like the consolidation of the northeast quadrant as an area of African American building ownership and residence in the late 1860’s, the establishment of the southwest quadrant as a residential area for Black industrial workers along the Reading Road and Railroad corridor along the western border of the neighborhood owed a great deal to Gordon’s vision for his community during the age of what WEB Dubois would later dub “Black Reconstruction.”

The Gordons and self-care by the African American Community in Walnut Hills

Even before their move to Walnut Hills, the Gordons had become members of Allen Temple, the AME church at Sixth and Main. The church’s 1874 history noted that on the eve of the Civil War “The treatment of colored people grew worse. … Many were the conflicts with the fiends of slavery.” After Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation “the iron doors of oppression stood ajar, and the sons and daughters of oppression came … and many of them settled in this city.” The congregation opened a hospital behind the church and served as a conduit for the distribution of government-supplied food to self-liberated enslaved people known as the Contrabands, and then, after the Emancipation proclamation, to the Freedmen.

In May 1861, just six weeks after the Confederate attack of Fort Sumter began the Civil War, Robert Gordon made a donation of 25 bushels of coal to Cincinnati’s Military Hospital. During the war he converted his liquid assets to Union War Bonds – betting as it were on the North. And as the War came to an end, the women of Allen Temple A. M. E. Church “formed a society called the Freedmen’s Aid Society. Mrs. Eliza Gordon was President. The object of the association was to help the Freedmen from the South to find homes, and shelter all who had no place to go.” Mrs. Gordon’s husband, or course, was Robert. The Gordons would work to aid Freedmen, especially in their efforts to leave the old South, for the rest of their days.

The Union Army built a Military Hospital on what is now Van Buren Avenue, just north of Martin Luther King Drive and west of I 71, then as now near the border of Walnut Hills and Avondale. As those wounded soldiers who survived went home, the hospital was converted in 1865 to a Freedmen’s shelter, especially for women and children widowed or orphaned by the war. In an additional reconstruction service to the community, a branch of the Freedmen’s Bank in Cincinnati saw over $100,000 in deposits in 1866 alone!

As the inflow of refugees slowed, the building was converted again to accommodate the Colored Orphans’ Asylum relocated from the basin and expanded owing to the community of Freedmen. The Gordons, living in Walnut Hills on Elm Street, took an interest in each of these developments. Robert Gordon served as a trustee, a funder, and a fundraiser for the orphan’s asylum. He solicited significant funds from leading white businessmen as well as from the African American community.

The Gordons continued their charitable work to meet the needs of vulnerable African Americans beyond the orphan asylum to include homes for “old Men” and “Old Women” as well. The story of the old men’s home is convoluted. A white man named John T. Crawford who had served as a Union spy during the Civil War had been saved from the Confederates by an old Black man. A successful real estate investor, he allowed a “colony” of Black men to live in a house he owned in College Hill. In his will he left his estate, valued at well over $100,000 including a house with 18 acres in the same suburb, to endow “an Asylum for aged and indigent worthy colored men – preference given to those who have suffered the miseries of American slavery.” The will name Robert Gordon as an executor; the court appointed him, and Gordon put up a $10,000 bond to accept the role. Gordon was active in the dispersal of the real estate and defended it against claims by alleged illegitimate heirs. After Gordon’s death his son-in-law George Jackson took on the role of trustee. (In the twentieth century the home moved to Lincoln Avenue in Walnut Hills and still operates as the Lincoln Crawford Care Center.)

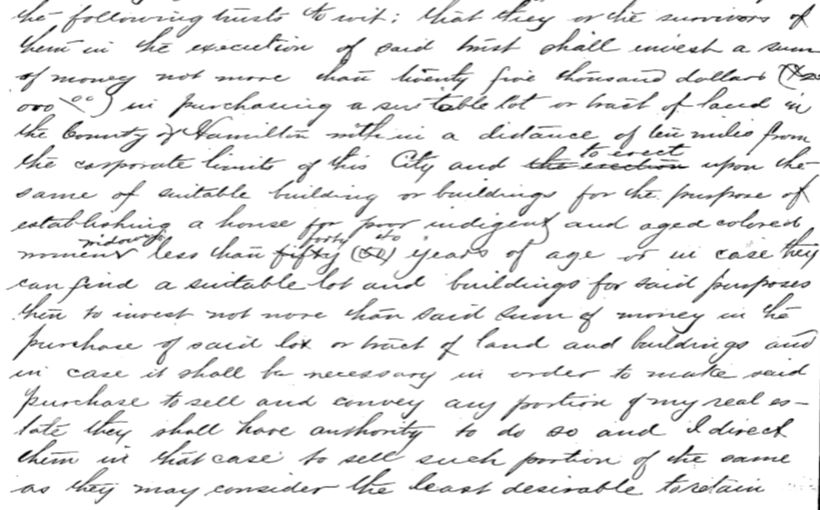

The Gordons decided to endow a similar home for women. Robert’s will provides a glimpse into the gender roles in wealthy families in the late nineteenth century. At the time it was drafted, daughter Virginia had married George Jackson, but the couple had no children. The will provided in any case an endowment of $25,000 for the “Gordon Home for Colored Widows.” Gordon’s wife Eliza and daughter Virginia were to serve as executors. (The will first specified Eliza and son-in-law George Jackson, but the latter was scratched out and replaced by his wife.) Income from the estate was to be split evenly between Eliza and Virginia. In the event that Virginia were to have a child or children – which she did – the estate was to pass after Eliza’s death to Virginia. In the event that Virginia had remained childless, Gordon’s estate (considerably larger than Crawford’s) would have become a trust to be administered by Jackson and the influential white lawyers Telford Groesbeck and Charles P. Taft, scions of established wealthy families who brought the same sort of integrity to the institution as Gordon brought to Crawford’s.

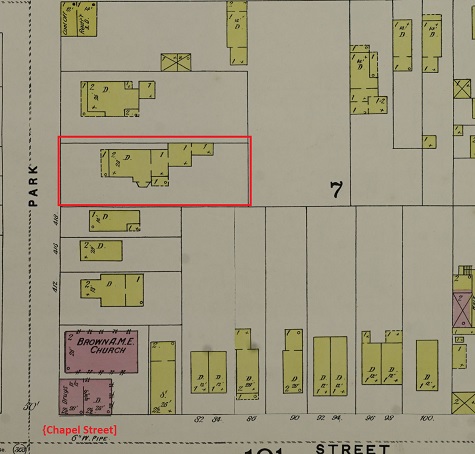

The widows’ asylum, generally known as the “Home for Aged Colored Women,” was located at what is now 2918 Park Avenue: at the time, in the middle of a block anchored by Brown Chapel AME Church and now a vacant lot next to First Baptist Church. Those two congregations were founded in the 1850’s as the First (Colored) Church of Walnut Hills and both have remained at the center of the Black community in Walnut Hills ever since.

Robert Gordon, the Colored Public Schools and the Black Community in Walnut Hills

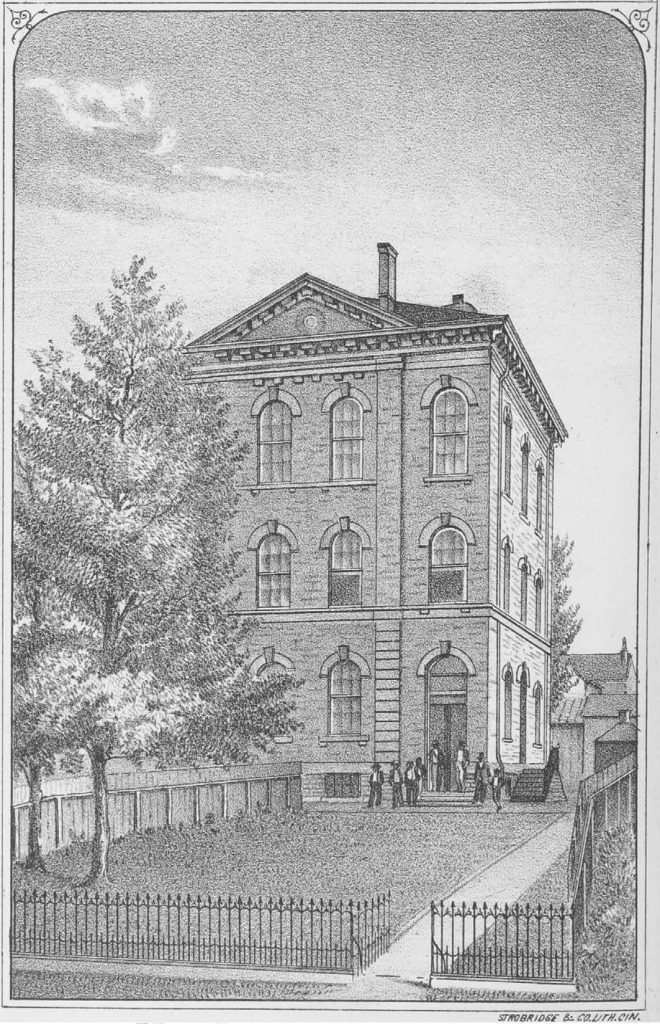

The Cincinnati Colored Schools emerged as a center of Black culture and community in the mid-nineteenth century, second only to churches. After a few false starts, the institution began its continuous existence in 1855. The annual reports of the Board of Trustees offer a goldmine of information about the community during the last decade before the Civil War and the early years of reconstruction. In 1873 the Colored Schools would come under the authority of the white School Board. Robert Gordon served on the Colored School Board during the last couple of years of the system’s self-government.

The first appearances of the Gordon family in the reports are those of daughter Virginia. In the wake of the Civil War, the Colored School Board established Gaines High School in 1866, named after the Gordon’s downtown neighbor John Gaines who died at the age of 38 in 1860. In the 1867-68 school year, and again in 1868-69, Virginia appeared high on the list of Meritorious Girls. (The Gaines Meritorious Students lists in the first decade of the school are something like a who’s who of the community for the next twenty-five years.) A couple of other names of Virginia’s classmates worth noting are Earnestine Clark (daughter of Gaines Principal Peter Clark), Andrew DeHart (later principal of the Elm Street Colored School in Walnut Hills), and George H. Jackson (from 1870 the teacher of drawing at Gaines) who twenty years later would marry Virginia Gordon.

Gaines High School, which also included a Normal School for the education of teachers, played an important role in the education of Freedmen. Its graduates staffed the growing Colored School system in Cincinnati and other schools in Southern Ohio and Northern Kentucky. Graduates, and even some who did not finish the course, staffed schools for the Freedmen’s Bureau and myriad church and charitable agencies for formerly enslaved children and adults who remained in the old South. Principal Peter Clark indeed complained in the mid-1860’s that teachers were in such demand that students left the school too early in order to accept positions.

Walnut Hills north of McMillan was annexed into Cincinnati in 1870; Robert Gordon’s house on Elm Street made him again a resident of Cincinnati. In 1871 he was elected to the Colored School Board. The 1871-72 Colored School Board Report, as we saw in the post about the development of Walnut Hills, noted that Robert Gordon sold $1974 worth of brick for the construction of the Elm Street Colored School. (This sort of self-dealing was absolutely normal in the years following the Civil War.) Gordon joined the committee for the Walnut Hills District, along with Hartwell Parham and Joseph Earley, charged with the Elm Street Colored School. Gordon lived a couple of blocks south of the school, while both Parham and Early occupied houses on the single-block Willow Street (now Preston) one block north and one block east of the new building.

The Parham and Earley families became pillars of the Black community in Walnut Hills for more than a century. Patriarch Hartwell Parham made a good living as a tobacco merchant downtown in the ante-bellum years; like Gordon, he moved to Walnut Hills after the Civil War. Their service together marks a shift of economic power and community leadership from the city in the basin to Walnut Hills. Hartwell’s son William H. Parham served as a principal and, from 1867, superintendent of the Colored Schools. William Parham too moved to Chapel Street in Walnut Hills. (Descendant Hartwell H. Parham would speak at the dedication of an elementary school named after his grandfather.)

Joseph Earley, still in his early twenties at the time of his election, would later serve the city as the first Black policemen and as an important figure in Republican politics during the Boss Cox era. Joseph’s father Dangerfield Earley had early served during the 1850’s as the pastor of the Colored First Church of Walnut Hills and ran a school for Black children in his Willow Street home before the annexation of Walnut Hills and the construction of the school on Elm Street. The colored School Board served as an institution to mentor and consolidate electoral politics and African American leadership in Cincinnati; Joseph got his start with his connections to Gordon and Hartwell Parham. Like the Parhams, many generations of Earleys would teach in the Cincinnati Public Schools: Maybelle Burke Earley retired from Frederick Douglass School, the successor to Elm Street, in 1975.

In addition to the subcommittee on the District School, Gordon served on the three-trustee committee for Gaines High School in 1871-71 and 1872-73. In this capacity he worked with principal Peter Clark, one of the most politically active Black Cincinnatians. While Clark occasionally formed alliances with socialists and even Democrats, he and other Gaines High School teachers most often joined with the Republicans – still the party of Lincoln. Gordon himself did not apparently seek leadership in the party, but he would serve on philanthropic committees with Clark and others in his circle.

In 1873, the Colored School Board was dissolved; the segregated school system continued, but under the supervision of the all-White Cincinnati School Board. Robert Gordon remained close to the leadership of the Black schools. Some sense of the closeness of the Gordon and Clark families emerges from the overlapping guest lists of their daughters’ weddings in the late 1870’s. Earnestine Clark, a teacher at Gaines, married fellow Gaines graduate Streeter Nesbitt (later a letter-carrier referred to as J. Street Nesbit); Virginia Gordon married George H. Jackson, also a Gaines graduate and teacher. Gordon had significant personal connection with at least two other long-time teachers at Gaines: Charles W. Bell taught handwriting, an essential skill for clerical workers; and Samuel W. Clark, also a successor to Gordon’s coal business with Wm. P. West.

Robert Gordon in National and State Politics

Gordon’s Bucktown neighbor Robert Harlan, who had moved to England in the late 1850’s, returned to Cincinnati after the Civil War. The wealthy pair had backgrounds about as different as possible for two formerly enslaved men of their generation. Harlan’s father was white; his mother was Mulatto; their son was light enough to “pass” was white, though he never did. Gordon was of very dark complexion. Harlan, while technically a slave, grew up in his wealthy household educated with the white sons, freedom of movement in both free and slave states, plenty of money and a taste for horse racing. Gordon enjoyed no such privileges. Both proved adept at business – we have seen that Gordon ran his enslaver’s coal yard, while Harlan made his fortune running his own store during the California gold rush, and training, racing and trading horses. Close connections between Gordon and Harlan would be cemented when Harlan’s son and Gordon’s son-in-law George Jackson became law partners.

The two men became important political allies, both devoted to the idea that Freedmen in the old south should migrate away from the old plantation economy. It took only about a decade for Reconstruction to come screeching to a halt in the old Confederate states. The plantation system converted itself from a slave economy to a sharecropping economy almost as brutal. With the end of the Grant administration in 1876 the Federal government withdrew its troops from the South. The Freedmen’s Bureau closed, the Freedmen’s Bank collapsed amid a scandal involving the Grant family, wiping out the $3.7 million in assets deposited by the African American community. (It is not clear how high the deposits in Cincinnati had risen between the $100,000 reported in 1866 and the 1874 failure, but it is safe to say the community lost what was to poor Black women and men a considerable fortune.)

Many formerly enslaved people decided it was better to leave the South than to stay under the evolving Jim Crow system. While Frederick Douglass urged the Freedmen to stay and resist, Gordon, Harlan and most of Cincinnati’s Black leadership instead advocated emigration to Western and Southwestern states. The peak of Black migration came in the late 1870’s. With clear Biblical overtones the refugees called their movement the “Exodus;” the most famous mass destination was Kansas and the migrants were often known as “Exodusters.”

Exodusters

The most prominent Cincinnati effort to assist the Freedmen hoping to leave the cotton and sugar state was the Homestead and Land Association. George Washington Williams, the pastor of the African American Union Baptist Church, proposed the organization in 1877. A committee headed by George Hayes organized the Association. It named the first Cincinnati Colored School teacher Peter Clark as its president, another schoolteacher, Andrew J. Dehart, as Assistant Secretary, and Robert Gordon as treasurer. It sold memberships in Cincinnati “with a view to colonizing in some Western or Southwestern State.” Clark’s students at Gaines High School raised $75!

The Homestead and Land Corporation opened one more chapter in Robert Gordon’s career. George Washington Williams was a complicated character of many contradictions who inspired a wonderful biography by John Hope Franklin, one of the parents of Black History. Williams came to Cincinnati in 1876; his fiery preaching revitalized the old Union Baptist Church. Williams soon studied law with Alphonso Taft and took the state bar exam at the same time as Alphonso’s son William Howard Taft. In 1880, just four years after he arrived in the city, Williams was the first African American elected to the state legislature. He got off to a solid start, active in the Republican caucus and busy with legislation supported by the delegation from Hamilton County. He also landed a job as secretary to state Senator Charles Fleischman, a tremendously wealthy white yeast manufacturer who tended to his business in Cincinnati was well as his legislative duties.

Williams got himself into serious trouble with his Black constituents. He introduced a seemingly innocuous bill suggested by white constituents from the Village of Avondale, Fleischman’s home turf. The bill gave the village health department the right to close cemeteries if it judged them a disease risk. Officials deemed the Colored American Cemetery in Avondale a threat under the new law. The coffins in closed Black cemetery were dug up and removed for reburial elsewhere. (The adjacent German Protestant Cemetery in Avondale was allowed to stay open. Note that the Walnut Hills Cemetery was at that time called the Second German Protestant Cemetery.)

The fury of the Black community was fierce and immediate. Robert Gordon, a trustee of the closed burial grounds along with Peter Clark (both strong supporters of Williams’ candidacy) led the charge. Williams disappeared from Hamilton County politics after this single term expired. He went on to write a two-volume history African Americans in the United States, beginning with the story of enslaved Africans in 1619, whose four hundredth anniversary we are observing this year; he later visited Belgium and the Belgian Congo and published the first blistering criticism of King Leopold’s brutal exploitation, but that story is far from Cincinnati and from Robert Gordon.

Closer to our topic, Washington’s term in the legislature representing Hamilton County set a precedent both for a single Black legislator from Cincinnati and for a number of years a single term for that Black representative dictated by the local Republican party. Both Robert Harlan and Gordon’s son-in-law George Jackson would serve in that seat in the late 1880’s. George Hayes, another leader in the Black opposition to Williams, was elected to the legislature in 1901 and broke the Republican stranglehold on Black influence and power; he served three terms.

References:

Most modern accounts of Gordon’s life derive from Carter G. Woodson’s many retellings, beginning with the first article in his Journal of Negro History: “The Negroes of Cincinnati Prior to the Civil War,” v. 1 no. 1, January 1916, pp. 1-22. Gordon is mentioned on pp. 21-22. Woodson in turn provides a footnote stating “For the leading facts concerning the life of Robert Gordon I have depended on the statements of his children and acquaintances and on the various directories and documents giving evidence concerning the business men of Cincinnati.” Woodson’s most complete account, intended for school children, appeared as “Robert Gordon a Successful Business Man”, The Negro History Bulletin, Vol. 1 No. 2, November 1937, pp 1, 3.

Another important source is Wendel P. Dabney, Cincinnati’s Colored Citizens. (1926) Gordon merits several mentions; the most important is a full-page sketch “A Napoleon of Finance,” p. 71. Dabney also noted Gordon served on the colored school board, p. 109. There is another passing mention on p. 142. More information will appear in a later section of this post.

Gordon does not appear in the most important biographical collection of nineteenth-century African Americans, William Simmons Men of Mark (1887), or (more surprisingly) in George Washington William’s History of the Negro Race in America From 1619 to 1800 (vol 1) and 1800–1880 (vol 2): Negroes As Slaves, As Soldiers, and As Citizens (1882).

Census records for Robert Eliza, and Virginia Gordon:

“United States Census, 1850,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-DBBQ-WGW?cc=1401638&wc=95RQ-DP6%3A1031310001%2C1031474401%2C1033778601 : 9 April 2016), Ohio > Hamilton > Cincinnati, ward 1 > image 31 of 166; citing NARA microfilm publication M432 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.). The 1850 census incorrectly lists Gordon’s birth state as Kentucky; all subsequent forms show Virginia. Gordon’s record appears in the forms for the First Ward.

“United States Census, 1860,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9BS6-9XW2?cc=1473181&wc=7QGH-BVV%3A1589432777%2C1589423456%2C1589433658 : 24 March 2017), Ohio > Hamilton > 13th Ward Cincinnati > image 157 of 189; from “1860 U.S. Federal Census – Population,” database, Fold3.com (http://www.fold3.com : n.d.); citing NARA microfilm publication M653 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.). The FamilySearch transcription erroneously lists the family name as “Jordon”. Gordon’s record appears in the 13th Ward, indicating new boundaries rather than a change of residence.

“United States Census, 1870,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-DZK7-M5J?cc=1438024&wc=92VB-FM7%3A518654901%2C518812101%2C519349801 : 14 June 2019), Ohio > Hamilton > Cincinnati, ward 22 > image 5 of 62; citing NARA microfilm publication M593 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.). The Walnut Hills residence was in the 22nd Ward

“United States Census, 1880,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9YBL-G15?cc=1417683&wc=QZ24-N2D%3A1589410656%2C1589399637%2C1589402432%2C1589395012 : 24 December 2015), Ohio > Hamilton > Cincinnati > ED 113 > image 1 of 66; citing NARA microfilm publication T9, (National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., n.d.) Gordon’s Walnut Hills residence was then in Ward 2.

Gordon’s wedding license is available at https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:9392-91Q2-J?i=240&cc=1614804

Property records are in the deed books for Hamilton County, which are available on line through FamilySearch.

Property at Eighth and Canal purchased 1 November 1848 from Henry Spencer for $2000, Deed Book 136 page 305, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C37L-597P-4?i=512&cat=293030 frame 513

Property at Sixth and Culvert purchased 11 May 1853 from Clark Williams for $2250, Deed Book 187 page 417, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C37P-L9GX-M?i=544&cat=293030 frame 545

“A recent tour in Ohio,” The Anti-Slavery Bugle, December 13, 1856, reprints a letter from the Liberator, sign with the intials W. C. N. Online at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83035487/1856-12-13/ed-1/seq-1/#date1=1825&index=18&rows=20&searchType=basic&sequence=0&state=Ohio&date2=1885&y=0&x=0&dateFilterType=yearRange&page=1