We have been looking at the Census data from 1870 and 1880 to understand the people who lived on what became Lincoln Avenue in 1877. The last post looked at women in 1870; this one will look at men. The most striking gender difference comes in the variety of occupations assigned by the census taker to men – even when we group together activities like driving a cart or wagon. On Lincoln Avenue there were half again as many occupations listed for men than for women, despite the fact that there were more women than men. The larger variety of jobs held for both Black and white adults. These ratios proved even larger for Ward 22 – all Walnut Hills – where men’s occupation counts were more than double that for women.

The single largest occupation listed for both Black and white men was “Daily Laborer” – unskilled physical work with no guarantee of steady employment. Something over a third of the 31 Black men on Lincoln Avenue had this job title, compared only a fifth of the 20 white men. Lumping rather than splitting other male occupations, we find main jobs in construction (6 black and 5 white men worked as plasterers, whitewashers and carpenters) and driving horse-drawn vehicles (6 Black and 4 white men drove teams or wagons or worked as coachmen or even as the driver of a horse-drawn omnibus). This local work with horses or mules was not the only employment in transportation. Two Black men on Lincoln worked as steamboat hands, and a third as a steward. (We shall return to the steamboat trade in another post.) Two Black men worked in farming in 1870; a decade later only one of them remained in Walnut Hills, and he had become a day laborer.

The single largest occupation listed for both Black and white men was “Daily Laborer” – unskilled physical work with no guarantee of steady employment. Something over a third of the 31 Black men on Lincoln Avenue had this job title, compared only a fifth of the 20 white men. Lumping rather than splitting other male occupations, we find main jobs in construction (6 black and 5 white men worked as plasterers, whitewashers and carpenters) and driving horse-drawn vehicles (6 Black and 4 white men drove teams or wagons or worked as coachmen or even as the driver of a horse-drawn omnibus). This local work with horses or mules was not the only employment in transportation. Two Black men on Lincoln worked as steamboat hands, and a third as a steward. (We shall return to the steamboat trade in another post.) Two Black men worked in farming in 1870; a decade later only one of them remained in Walnut Hills, and he had become a day laborer.The remaining men had miscellaneous occupations. One Black man made his living as a music teacher (Samuel White, born free in New Jersey in 1801) and another, Isaac Troy, was a porter in a bank, a position he would still hold in 1880. The other white men on Lincoln Avenue were also in one-off occupations: a blacksmith, a shopkeeper, a livestock dealer, a clerk, a policeman and a saloonkeeper. There was a lone sculptor on the street: Louis Rebisso, an Italian immigrant, who seemingly settled in Walnut Hills around the time of the census. (We shall return to Rebisso in another post.)

In the larger sample of Ward 22, which included most of Walnut Hills, there are a couple of additional job descriptions with more than a few practitioners. Thirty-seven white men (and 6 white women) worked at shoemaking, destined to be a major industry in Cincinnati. Thirteen white and two Black men worked as clergymen; these totals for the most part do not include the faculty and students at Lane Seminary. Dangerfield Earley, founder of the African American First Church, later the First Baptist Church of Walnut Hills, had been preaching since the mid-1850s and remained in his home on Willow Street (now Preston) until his death in 1883. In 1870, he owned property valued at $7,000.

As on Lincoln Avenue, most Black men in the rest of Walnut Hills were daily laborers; more white men held that description than almost any other. The most striking related job classification, perhaps, is “Grading Street,” work much like that of daily laborers. It was hard physical labor but provided steady employment. Moreover, it constituted a significant municipal workforce; it was among the first working-class political patronage positions for the vastly expanding city government. Three Black and twenty white men from Walnut Hills landed these jobs with the city – already in 1870 the African American community had some political clout. Most if not all of them presumably laboring to accomplish something of an engineering marvel building the 100 foot wide Gilbert Avenue, still a magnificent straight, flat, spacious route from the city basin to Walnut Hills and points north and east. As the neighborhood developed, especially after its incorporation into Cincinnati in 1872, many more grading projects flattened and straightened existing and new roads.

This brief sketch shows us a new face of the neighborhood at the optimistic beginnings of post-Civil War Reconstruction. The estates of wealthy Cincinnatians escaping the stench and noise of the city basin and the intellectual Calvinist community around Lane Theological Seminary was joined by the diverse African American and immigrant working-class community of Lincoln Avenue in 1870.

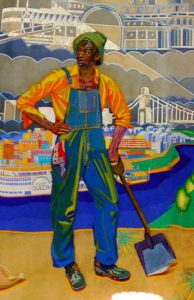

The illustration is from the mural in the rotunda of the Union Terminal.

– Geoff Sutton