Most African American women in Walnut Hills took in laundry during the Reconstruction era, roughly 1865-1880. The work was punishing, but the washerwoman was her own boss; she worked in her home or yard. The vicissitudes of the weather and the normal weekly cycle from pick-up to delivery allowed some flexibility in scheduling. Down-time, for example as the clean clothes dried on the line, permitted some time for care of children, cooking, cleaning, and other household chores – if not for much in the way of leisure. We have seen how the introduction of steam-powered laundries competed with the traditional hand washboard wooden tubs.

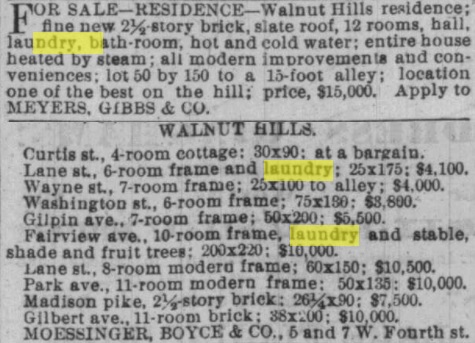

A second technological innovation imposed a different type of disruption. Beginning in the early 1870s, manufacturers of metal machinery developed new home equipment for cleaning, drying, and ironing clothes. We can follow this development in Cincinnati business directories, and the real-estate and help-wanted advertisements in newspapers. Just as Walnut Hills real estate took off in the years after the Civil War, builders began to install laundry and drying rooms in the basements of the homes of the wealthy. I grew up in such a house in our neighborhood built in the 1880s and a hundred years later my mother was still drying clothes in a cabinet dryer, converted in the 1920s for gas heat.

The lady of the house in earlier, grander days did not venture down into her basement. Instead, she “hired in help” to operate the industrial-strength equipment. (The sort of consumer washers and dryers now in use came in mostly in the 1920s through the ‘50s.) The most important result of this change came in the role of the washerwoman. Emancipation had allowed her to escape not only the bondage of slavery; it made her an independent businessperson serving multiple clients. She was in no sense a servant.

The lady of the house in earlier, grander days did not venture down into her basement. Instead, she “hired in help” to operate the industrial-strength equipment. (The sort of consumer washers and dryers now in use came in mostly in the 1920s through the ‘50s.) The most important result of this change came in the role of the washerwoman. Emancipation had allowed her to escape not only the bondage of slavery; it made her an independent businessperson serving multiple clients. She was in no sense a servant.

The installation of laundry apparatus in upper-middle-class home radically altered the relationship between the owner of the soiled articles and the woman who washed them. The washerwoman entered into the home of a wealthy family, and rather than being paid by the piece or the pound she earned daily or weekly wages. Moreover, the rhythm of laundry work – the initial long soak in hot water, the drying time in a heated sheet metal closet that provided the time for the independent worker to accomplish her own household responsibilities – made it inevitable that the worker would also spend time cleaning the house. The women’s help wanted ads, and situations wanted ads, increasingly specified laundry and cleaning as paired work.

The relationship between the washerwoman and the client reverted to that of servant and mistress. Instead of a weekly pickup and drop off, usually mediated by someone hired by the washerwoman, the domestic worker toiled under constant supervision. She also worked in the intimate setting of someone else’s home, with all the lack of privacy and imposed discretion that entailed.