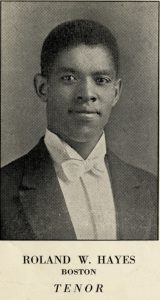

In 1916, the (white) Cincinnati Commercial Tribune newspaper reviewed a “splendid” musical performance by the Douglass Choral Society. The reviewer observed that the group presented the concert “with the aim of bringing before the public the possibilities of the public school as a social center to promote musical instruction and appreciation among the members of the community in general.” The paper announced a few days before that the Society, “under the direction of Evermont P. Robinson, will give a concert at the Douglass School auditorium … The chief feature of the program is ‘Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast,’ Longfellow’s poem, set to music by S. Coleridge-Taylor, England’s late negro composer. Roland W. Hayes, tenor, of Boston, is to be the soloist of the evening.” The performance at the segregated school in Walnut Hills might be celebrated as a triumph of African American culture. I would prefer to think of it as a thoroughly American high culture that happened to be performed within our Black community – the only setting in the city capable of mastery of and appreciation for the work.

In 1916, the (white) Cincinnati Commercial Tribune newspaper reviewed a “splendid” musical performance by the Douglass Choral Society. The reviewer observed that the group presented the concert “with the aim of bringing before the public the possibilities of the public school as a social center to promote musical instruction and appreciation among the members of the community in general.” The paper announced a few days before that the Society, “under the direction of Evermont P. Robinson, will give a concert at the Douglass School auditorium … The chief feature of the program is ‘Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast,’ Longfellow’s poem, set to music by S. Coleridge-Taylor, England’s late negro composer. Roland W. Hayes, tenor, of Boston, is to be the soloist of the evening.” The performance at the segregated school in Walnut Hills might be celebrated as a triumph of African American culture. I would prefer to think of it as a thoroughly American high culture that happened to be performed within our Black community – the only setting in the city capable of mastery of and appreciation for the work.

The composers on the program, in addition to the Anglo-African Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (and the token white Giuseppe Verdi), included African Americans Henry Thacker (“Harry”) Burleigh, J. Rosamond Johnson, and Will Marion Cook. Featured soloist Rowland Hayes often sang tenor to Harry Burleigh’s baritone on stage; the two were among the first African Americans to break into the classical concert and recording industries, a generation before Paul Robeson and Marian Anderson.

Concert director Evermont P. Robinson, born near Lexington, had found his way to Howard University in Washington DC, graduating in 1911. He next worked for two years as the musical director for the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation in the State of New Jersey – a plum (though poorly paid) assignment for an up-and-coming Black musician. In the summer of 1915, he served briefly as Professor of Music at the Lincoln Institute – later University – in Jefferson City, Missouri. Yet Cincinnati’s Frederick Douglass School competed for academic talent with Historically Black Colleges. Evermont Robinson gave up his position in the Missouri College to teach here.

The attractions of the Queen City further included a family connection. We have met Evermont’s brother Dr. James H. Robinson, himself a 1911 graduate of Fisk University, who earned a master’s at Yale in 1914 and eventually a Ph. D. in sociology. James, like Evermont immensely over-qualified for the position, started his career as a teacher at Douglass in 1915. It turned out that James served as the pianist (both soloist and accompanist) at the Choral Society concert. (In line with the goal to promote musical instruction and appreciation he also delivered a lecture on “The Value of Negro Music.”)

“Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast” was hardly a typical high school musical. The Douglass program would have been progressive in Harlem, just launching its Renaissance at the time. Nonetheless there was an audience in Walnut Hills for this modern, American classical music. It was appropriate that a concert steeped in what were then called Negro Spirituals came to Douglass School in Walnut Hills, originally called the Elm Street Colored School when built in 1870. Andrew J. DeHart (himself a product of the Cincinnati Colored Public Schools) served as principal from 1886 until his death in 1909. Under DeHart’s leadership in the nineteen aughts, the School took the name Frederick Douglass after the great Black abolitionist and civil right leader.

Principal DeHart had spent the early 1880s in Tennessee as a minister. He married Jennie Jackson, the lead soprano of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, a concert choir sent out by the Fisk Free Colored School (later University) in Nashville in 1871. Jenny Jackson DeHart moved with her husband to Cincinnati in 1885 but continued as a headliner for various travelling incarnations of the Jubilee Singers into the 1890s. In addition to a classical European repertoire, the Singers performed their own four-part choral arrangements of traditional Black songs. Mrs. DeHart had a busy singing schedule in Cincinnati’s Black churches and other cultural institutions until shortly before her own passing in 1910, a year after her husband. The community knew the spiritual repertoire intimately.

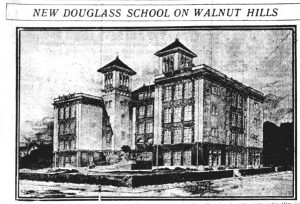

Shortly after A. J. DeHart’s death in 1909, a new Frederick Douglass School building went up on the same block in 1911, now Alms Place and Chapel. A monument to the Progressive Era as well as to DeHart, the new, still segregated school included a kitchen and dining room serving a penny lunch, showers for boys and girls with gender-appropriate attendants, and a health office staffed by the Cincinnati Health Department. The design also included facilities for adults in the community. The School Library had a separate street entrance; Lucile Pitts served as Cincinnati’s first Black librarian for children during the day and for adults in the evening. A 350-seat auditorium served both the school and the community.

Shortly after A. J. DeHart’s death in 1909, a new Frederick Douglass School building went up on the same block in 1911, now Alms Place and Chapel. A monument to the Progressive Era as well as to DeHart, the new, still segregated school included a kitchen and dining room serving a penny lunch, showers for boys and girls with gender-appropriate attendants, and a health office staffed by the Cincinnati Health Department. The design also included facilities for adults in the community. The School Library had a separate street entrance; Lucile Pitts served as Cincinnati’s first Black librarian for children during the day and for adults in the evening. A 350-seat auditorium served both the school and the community.

The public around the school certainly was prepared to appreciate the concert in that auditorium. Anglo-African composer Coleridge-Taylor had learned a great deal about the Spiritual – and from the same source as the community in Walnut Hills. He had heard the Jubilee Singers during their annual summer concerts in London during the 1890s. The headline piece on the 1916 program was Coleridge-Taylor’s most famous choral work – a curious amalgam of things American. The title, the Song of Hiawatha, came from the poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, wildly popular in the US and Britain. Longfellow’s 1855 epic offered a romantic celebration of the Ojibwe Indian Hiawatha and his Dakota wife Minnehaha. (Within a decade, in one of the darker moments of Abraham Lincoln’s presidency, both tribes were nearly exterminated and consigned to small reservations.) Yet in the manner of medieval epics, Longfellow invented a past creating a Native foundation for the American experience.

Coleridge-Taylor encountered the poem in the late 1890s and set it to music based on American themes as he understood them. His Classical cantatas based on Longfellow’s poem drew heavily on melodies he had explored in piano arrangements of 24 Spirituals. An overture to Hiawatha followed in 1901, based on musical themes from “Nobody knows the Trouble I’ve Seen.” The Douglass performance in 1916 indeed included costumes for the chorus, and a Miss Margaret Davis performing the “Beggar’s Dance.”

Geoff Sutton